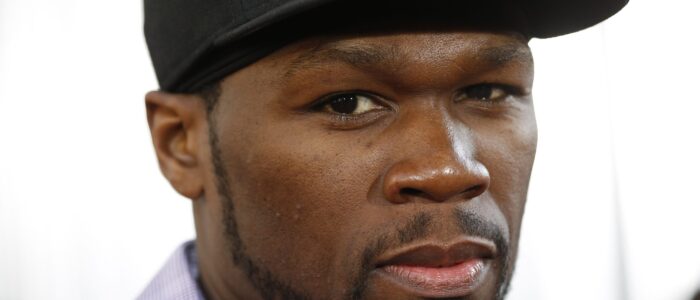

Such religious language and rhetoric is not limited to talk of “god” or gods. Outside of the NGE, and outside of the musical side of hip-hop, religious language continues to be reappropriated for the sake of reclaiming humanity. Multiplatinum recording artist 50 Cent’s book The 50th Law stands as an example. Co-written with self-help guru Robert Greene, the book is literally packaged as if a sacred text. Ornate lettering, and constant shout-outs to some of history’s wisest figures, come together to present what I recently described as “a metaphysics of self-help” (Miller, What is Humanism, 90). Here, the outlaw status of 50 cent (he was a hustler, after all) is applied to the topic of fear. Trumpeted as a type of new age metaphysical response to overcoming fear, the book offers no less than a guide to carving out one’s destiny in the business world, personal spaces, creative outlets and all avenues of life. Combining this new age blueprint for overcoming fear with a constant use of “religious” rhetoric and icons to validate his argument, 50’s book is an example of a hip-hop humanism in practice. Only, 50 seems to imply that religious language and its continued significance might be worth keeping for (at least) selling books, and (at most) using wisdom learned from religion(s) as a means of overcoming fear. This tendency to keep such rhetorical and marketing strategies is common in hip-hop. Concern over god or whether religion is good or bad is of far less concern than making one’s presence known to the society and the world. We see a pragmatic humanism engaging in a “by any means necessary” process of self-definition and re-humanization of black bodies and black options in the face of a society that has been much more comfortable believing in “god” than in the human worth of African Americans.

Such religious language and rhetoric is not limited to talk of “god” or gods. Outside of the NGE, and outside of the musical side of hip-hop, religious language continues to be reappropriated for the sake of reclaiming humanity. Multiplatinum recording artist 50 Cent’s book The 50th Law stands as an example. Co-written with self-help guru Robert Greene, the book is literally packaged as if a sacred text. Ornate lettering, and constant shout-outs to some of history’s wisest figures, come together to present what I recently described as “a metaphysics of self-help” (Miller, What is Humanism, 90). Here, the outlaw status of 50 cent (he was a hustler, after all) is applied to the topic of fear. Trumpeted as a type of new age metaphysical response to overcoming fear, the book offers no less than a guide to carving out one’s destiny in the business world, personal spaces, creative outlets and all avenues of life. Combining this new age blueprint for overcoming fear with a constant use of “religious” rhetoric and icons to validate his argument, 50’s book is an example of a hip-hop humanism in practice. Only, 50 seems to imply that religious language and its continued significance might be worth keeping for (at least) selling books, and (at most) using wisdom learned from religion(s) as a means of overcoming fear. This tendency to keep such rhetorical and marketing strategies is common in hip-hop. Concern over god or whether religion is good or bad is of far less concern than making one’s presence known to the society and the world. We see a pragmatic humanism engaging in a “by any means necessary” process of self-definition and re-humanization of black bodies and black options in the face of a society that has been much more comfortable believing in “god” than in the human worth of African Americans.