A Visionary Story: The History of NACH and The Humanist Institute

by Carol Wintermute (written February 2014)

To begin our visionary story, the history of The Humanist Institute, we need a cast of characters. The starring personalities were, and some still are, leaders of various humanist groups across a continuum from religious humanists to secular humanists. They were Sherwin Wine from the Society for Humanistic Judaism, Howard Radest from American Ethical Union, Khoren Arisian from American Ethical Union, Paul Beattie from the Unitarian Universalist Humanist group (known earlier as the Fellowship of Religious Humanists), and Paul Kurtz from the Council for Secular Humanism.

To begin our visionary story, the history of The Humanist Institute, we need a cast of characters. The starring personalities were, and some still are, leaders of various humanist groups across a continuum from religious humanists to secular humanists. They were Sherwin Wine from the Society for Humanistic Judaism, Howard Radest from American Ethical Union, Khoren Arisian from American Ethical Union, Paul Beattie from the Unitarian Universalist Humanist group (known earlier as the Fellowship of Religious Humanists), and Paul Kurtz from the Council for Secular Humanism.

In 1976, Paul Beattie developed a vision. He dreamt of pooling the talents and resources of various existing humanist groups in North America to create an organization that could more effectively promote the humanist movement. The others were on the same wavelength.

They often met at International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU) World Congresses and discussed the North America humanist situation. In the late ’70s and early ’80s, they met in London, Brussels, and Hanover. The IHEU is an organization of humanist groups from around the world. The Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA), HUUmanists (UUHA), American Humanist Association (AHA), American Ethical Union (AEU), Rationalist Society, and Council for Secular Humanist (CSH) are currently some of its members.

Sherwin Wine proposed in 1982 that they establish a humanist school in North America for training humanist leaders. He said, “The greatest need of humanism today is the presence of well-trained leaders who will be able to mobilize people to embrace our philosophy of life.”

Sherwin Wine proposed in 1982 that they establish a humanist school in North America for training humanist leaders. He said, “The greatest need of humanism today is the presence of well-trained leaders who will be able to mobilize people to embrace our philosophy of life.”

Everyone recognized that the leaders of various humanist groups were getting older and there were not many replacements in the wings.

At this time the fortunes of humanism in North America were declining. Increasing number of Americans who repudiated traditional religion were turning to New Age religions and a search for “spirituality.” The Moral Majority was at its height. Secular living without commitment to a secular philosophy of life was the dominant mode of most non-religious people. The humanist wing of the Unitarian movement, dominant in the Midwest, was collapsing because humanist ministers were aging and dying and there were no replacements. Some new pragmatic effort to strengthen humanism was needed to reverse the decline.

The conversation amongst our founders was a response to the urgent need to defend humanism against the assaults of its enemies and to find an effective way to bring the message of humanism to a wider public. The emerging plan featured two steps. The first was a coordinating committee representing all humanist organizations in North America. Thus the North American Committee for Humanism (NACH) was born. The second step was the establishment of a school for the training of humanist leaders. Thus the idea of The Humanist Institute (THI) was born.

While many Unitarian ministers had become humanist leaders, and while the Ethical movement had created a program to train their own community guides, there was no strong sense of a profession designated “humanist leader.” And there was professional collegiality that crossed boundaries of historic groups. Unitarian humanist ministers in particular spent a significant amount of time connecting to non-humanists in their denomination and very little time connecting with leaders outside their movement who shared their conviction. The same was true for Humanistic Jews.

While many Unitarian ministers had become humanist leaders, and while the Ethical movement had created a program to train their own community guides, there was no strong sense of a profession designated “humanist leader.” And there was professional collegiality that crossed boundaries of historic groups. Unitarian humanist ministers in particular spent a significant amount of time connecting to non-humanists in their denomination and very little time connecting with leaders outside their movement who shared their conviction. The same was true for Humanistic Jews.

Sherwin, Howard, and Jean Kotkin (AEU) contacted the leaders of the humanist group in the United States and Canada. They received many enthusiastic responses to Sherwin’s proposal for a meeting. The time seemed right, so in late August of 1982, 45 people assembled at the Center for Continuing Education at the University of Chicago.

The organizing committee of NACH consisted of the following: Khoren Arisian, Paul Beattie, Ed Ericson, Paul Kurtz, Howard Radest, Lyle Simpson, and Sherwin Wine.

The meeting was filled with energy and enthusiasm, I was working with Khoren Arisian as the Education Director at the First Unitarian Society of Minneapolis and was invited by him to attend the meeting. Several Meadville-Lombard students present at the meeting pleaded for humanist education, which was neglected part of their curriculum. Even though I was new to all of this, I could still tell that something important was happening.

The meeting was filled with energy and enthusiasm, I was working with Khoren Arisian as the Education Director at the First Unitarian Society of Minneapolis and was invited by him to attend the meeting. Several Meadville-Lombard students present at the meeting pleaded for humanist education, which was neglected part of their curriculum. Even though I was new to all of this, I could still tell that something important was happening.

Sherwin, as the dynamic force behind this development, was elected chairperson of the NACH board and others were nominated to serve as Directors. It didn’t take but a moment for the women at the meeting to notice that all the Directors were men. Thus feminist humanists made their first stand to be included. Miriam Jerris (SHJ) and Jean Kotkin were added to the list that included Khoren Arisian and Howard Radest, Vice Presidents, Paul Beattie, Secretary, Alfred Cook, Treasurer, Robert Davis, Ed Ericson, Roy Fairfield, Roger Greeley, John Hoad, Paul Kurtz, Lyle Simpson, and Gordon Stein.

The group immediately defined the mission of the new organization. The key objective was leadership education. Obvious to all assembled was the need for training leaders to fill spots for the coming generations. Some of the participants were from groups that had no training programs, or barely adequate programs. Others had programs that needed supplementation or had leaders who were trained in university/seminary programs that never mentioned humanism. Unfortunately, this situation is still true. We knew then, as we know now, that if we were in need of well-trained professionals and lay people to carry on the work of the humanist movement, we had to do it ourselves. Today, some of our humanist organizations have developed their own training program, but the Institute is the only one that covers the whole continuum of humanist thought and philosophy in-depth.

The group immediately defined the mission of the new organization. The key objective was leadership education. Obvious to all assembled was the need for training leaders to fill spots for the coming generations. Some of the participants were from groups that had no training programs, or barely adequate programs. Others had programs that needed supplementation or had leaders who were trained in university/seminary programs that never mentioned humanism. Unfortunately, this situation is still true. We knew then, as we know now, that if we were in need of well-trained professionals and lay people to carry on the work of the humanist movement, we had to do it ourselves. Today, some of our humanist organizations have developed their own training program, but the Institute is the only one that covers the whole continuum of humanist thought and philosophy in-depth.

It was Edwin Wilson, the Dean of American Humanism at the time, who formally proposed that we create a leadership training school. The proposal was supported unanimously.

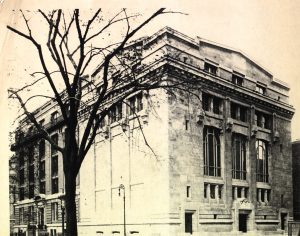

Howard Radest was asked to be the Dean of the new Humanist Institute. He says he reluctantly agreed, but it was obvious that he was the person to do this job. Khoren Arisian volunteered to be the Associate Dean. The New York Society for Ethical Culture offered its meeting house to be the home of the Institute. Now that the Board was chosen, prospective students were informally contacted. I feel very fortunate to have been one of those.

Howard Radest was asked to be the Dean of the new Humanist Institute. He says he reluctantly agreed, but it was obvious that he was the person to do this job. Khoren Arisian volunteered to be the Associate Dean. The New York Society for Ethical Culture offered its meeting house to be the home of the Institute. Now that the Board was chosen, prospective students were informally contacted. I feel very fortunate to have been one of those.

As always, money needed to be raised to fund this program. The first gift of $50,000 was provided by Werner Klugman of the AEU. Others quickly followed. Roger Greeley, Minister of the Unitarian Society of Kalamazoo, Michigan solicited a wealthy friend of his society to contribute $200,000. Later he added another $150,000. With the money in hand, Dean and Associate Dean appointed, and students recruited, everything was moving into place.

In March 1984, The Humanist Institute was launched. The first class with students from AEU, AHA, UUA, and SHJ gathered in New York at the Ethical Culture Society for the first seminar with Howard Radest as mentor. It was the first trans-denominational, trans-humanist organization program for the education of humanist leaders. It was a graduate program. A few students have been part of the program while they worked on completing their college degrees.

To launch this enterprise in less than two years was a surprising feat. Some organizations provided scholarships; others provided classroom space, and members of all the groups had to be solicited for financial support. Jean Kotkin and Roger Greeley raised enough money to see us through the next decade.

Howard Radest created the curriculum, which is still the foundation of what we do today. As a member of the first class, I was one of the guinea pigs for this program. The idea was to immerse us in humanist history and philosophy, learn about the various forms of humanism in North America, understand our movement in light of other religions and philosophical movements, understand moral and ethical development, examine our underpinnings of reason and science and then apply humanist thought to social, political and economic issues, as well as look at aesthetic aspects of human development and the practical issues of leadership.

Howard Radest created the curriculum, which is still the foundation of what we do today. As a member of the first class, I was one of the guinea pigs for this program. The idea was to immerse us in humanist history and philosophy, learn about the various forms of humanism in North America, understand our movement in light of other religions and philosophical movements, understand moral and ethical development, examine our underpinnings of reason and science and then apply humanist thought to social, political and economic issues, as well as look at aesthetic aspects of human development and the practical issues of leadership.

It was the most stimulating graduate experience I have ever had, including my graduate work on moral development and family social science.

In the early years, NACH also sponsored conferences where guest speakers were invited and students asked to respond to their presentations. We held these meetings not only in New York, but also in Minneapolis, Indianapolis, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, and Detroit; cities where there were significant numbers of members of our constituent groups. Many of these attendees became our benefactors after hearing testimonials to the value of the students’ experience. Because these meetings occurred each year of the program, the first class was stretched out to four years to complete the program. Due to time restrictions, and cost to organize these weekends, reluctantly, they were dropped.

Howard retired in 1992 after putting in ten years of considerable energy and deep thought into this program. His contribution is enormous. Bob Tapp was asked to be Dean following Howard. He was willing to lend his considerable knowledge and experience for the next 13 years, retiring in 2004. Kendyl Gibbons (First Unitarian Society of Minneapolis minister) and I began our tenure in August of that year. We were fortunate to have Bob steady at the helm the whole time. He even nudged us all into the internet age, which is a great plus for his foresight.

In 1985, a faculty colloquium began to meet annually. During Bob’s Deanship, more and more faculty members were selected for mentoring in the classroom and others were asked to join as contributors to a “think tank.” Faculty colloquia were organized around issues pertinent to humanists. As a result, we published 17 volumes of “Humanism Today,” the last three in hardcover with Prometheus Press.

In 1985, a faculty colloquium began to meet annually. During Bob’s Deanship, more and more faculty members were selected for mentoring in the classroom and others were asked to join as contributors to a “think tank.” Faculty colloquia were organized around issues pertinent to humanists. As a result, we published 17 volumes of “Humanism Today,” the last three in hardcover with Prometheus Press.

In the middle years, we tried to offer a three-level program with certificates of completion for year one, two, or three, but no one but no one took those options. It seems there was a dynamic operating that none of the founders took into consideration. Students during the first year share such an intense experience that the classes bonded into tightly-knit units. Some students may join in the first year and a few may leave for a variety of reasons, but those who remain become quite connected and do not want to miss any of the experience. I know that some of the people I met during my class experience are still good friends after 22 years.

I cannot foresee a future of strictly computer classes for THI, as the interpersonal factor in the learning environment is an invaluable feature of the program. It is the coming together of representatives of all our groups that will enable us to understand each other’s views and work together in the future. But we do now offer online courses, which were originally developed by the Institute for Humanist Studies. These online courses are reaching individuals in urban and remote areas bringing humanist thought and philosophy into homes across the globe.

Through experience we have learned that large classes, 15 and above, do not function well with our seminar format. Thus we try to limit our classes to no more than ten students, which ensures plenty of time for full participation by all class members.

In the early 1990s, we realized that NACH’s ambition to be the coalition organization for all humanist groups was not being fulfilled. Some groups wanted to be on their own. As we know, humanists do not always agree on the question of humanist secularity and religiousness. What we were doing well was the leadership training. Even if one or another group was not active in a given year or two, they were still represented by students in our classes.

In 1992, Sherwin Wine retired from the Presidency. It was an amazing ten-year term. Being on the Board most of this time, I saw first-hand what the force of a positive, can-do personality could accomplish, especially when combined with a master ability to mobilize others and model the way as a supreme articulator of the humanist message. What I loved the most about Sherwin was his irrepressible sense of humor and candid treatment of life’s absurdities. He was a fearless exponent and marvelous example of humanist leadership.

All of our founders are gifted people with an amazing array of talents, the foremost of which is their gift of articulating humanism in an exciting and compelling manner.

Suzanne Paul served as President the next year, following Sherwin and was followed in turn by Ron Solomon for a year. In 1994 I became President of NACH.

In 1992, Chuck Debrovner took over as the President of NACH’s subsidiary, The Humanist Institute. Sherwin had been head of both until then. After a few more years, we decided that it was time to review our vision, mission and purpose. It was now totally clear that our one true mission was leadership education and training. With that in mind, we decided to become one organization: NACH/THI. As a result, we were no longer a membership organization of individuals from the various constituent groups, but an educational enterprise with supporting associations. Chuck and I became Co-Presidents. It worked so well, we continued until I retired from the Co-Presidency in 2002.

In 1992, Chuck Debrovner took over as the President of NACH’s subsidiary, The Humanist Institute. Sherwin had been head of both until then. After a few more years, we decided that it was time to review our vision, mission and purpose. It was now totally clear that our one true mission was leadership education and training. With that in mind, we decided to become one organization: NACH/THI. As a result, we were no longer a membership organization of individuals from the various constituent groups, but an educational enterprise with supporting associations. Chuck and I became Co-Presidents. It worked so well, we continued until I retired from the Co-Presidency in 2002.

Also in December 2002, looking forward to our 25th year, the Board began a strategic planning process with Hank Wintermute as our consultant. Surveys were mailed to alums, faculty and our associate members. A final report was delivered in 2003 and it has been our guiding document, which just recently was reviewed with an eye to our progress toward our stated goals. One of these was to look at how well our curriculum served our leadership education and training purposes.

Kendyl and I worked with the past Deans, the education committee, and Board of Directors to update the curriculum. Class 14 was the first one to experience the revised program.

Some of the elements of the early years have been restored, such as a fieldwork component and written assignments, besides our final projects. An emphasis is being put on leadership, both theory and skills, to help students become effective at whatever aspect of humanism they choose for their arena of activity. We now call the program “leadership and education training.” We aim to combine our continued commitment to a strong and rigorous intellectual program with the practical and institutional so that students not only will be able to articulate and advocate humanist values and positions, but to be effective practitioners as well.

Warren Wolf took over as President of THI, after working with Chuck Debrovner as Co-President. We had the delightful pleasure of honoring Chuck on his retirement, but we did not let all that experience and wisdom get away as Chuck is still active on our Board of Directors and Executive Committee.

Warren Wolf took over as President of THI, after working with Chuck Debrovner as Co-President. We had the delightful pleasure of honoring Chuck on his retirement, but we did not let all that experience and wisdom get away as Chuck is still active on our Board of Directors and Executive Committee.

We were lucky to have someone with Warren’s skills and talents to lead us for nine years. He was a visionary who knew how to get things done and the perfect person to push us forward at a critical point in our history. Warren retired from the Presidency in 2010 turning the reins over to Jim Craig. Jim’s expertise as a lawyer, academic and President of the Unitarian Universalist Church of Sarasota Endowment Fund was a great asset in leading the Institute into a new era.

Today, we have over 150 graduates of the Institute. They are actively serving our movement as ministers, leaders, board members, organizational executives, elected officers, advocates, spokespersons, celebrants, and supporters. The majority of our board of directors consists of alumni chosen for their diverse skills and their activity in one or another of our humanist organizations. Many of us belong to several humanist groups because of our positive experience in getting to know these organizations.

A program like ours is never complete. We will continue to revise, update, and adjust to the times and culture, while retaining the tried and true. We are looking at expanding continuing education courses, regional seminars, courses on campus leadership, and work in hospitals as well as other options to enhance our vision of educating leaders who will carry our humanist message to the world and to attract others to keep our movement vital and influential in the public arena.